Most interviews go largely as expected. You arrange to meet someone and you talk to them in a peaceful environment free from distractions.

Margaret Bravo does things differently, in various ways. For example: she is still working at the age of 82. Still running St Peter’s Church Pre-School on Kingstown Road, Carlisle, 50 years after founding it.

And my plan to see Margaret in a quiet office quickly disappeared. Here we are in the classroom, plonked on tiny chairs, surrounded by girls and boys aged two to four.

My concern at the prospect of a chaotic interview soon melts away. The children are lovely. And I realise that this is the best way to see Margaret.

Over the next couple of hours I learn about her through her actions as well as her words.

Before registration, she talks to the children in her melodic Welsh accent about the lace top she is wearing.

“Can you see my arms? Yes? How? Because my top has got holes in! Should it go in the bin because it’s got holes in?”

Some little voices say no. Some say yes.

“No, it’s supposed to have holes in! It’s lace - that’s a new word.”

At St Peter’s Pre-School, this week’s letter is ‘s’.

“What’s in the sky today? That’s right - sun. What did I have for breakfast today? They’re long and brown. I had to fry them in a pan.”

One girl says “egg” before the answer is revealed.

(It’s sausages, by the way).

Long-serving deputy manager Ann Crabbe reads the register and waits to hear “Yes, Mrs Crabbe.”

Everyone here is long-serving. “In 50 years, I’ve had eight staff,” says Margaret.

After registration some of the children play outside. Margaret and I remain on our tiny chairs. She looks much younger than her age. There’s something childlike about her enthusiasm and her openness.

The pre-school operates on weekday mornings during term time. Margaret says she feels lonely when it’s closed.

“I don’t look forward to holidays. My husband died. I’ve no brothers and sisters left. One of my sons is a headteacher down south. The other has got his own company.

“People say ‘You’re not still working, Margaret?’ I really enjoy working. I love what I’m doing. I’m passionate about little ones. I enjoy seeing children learning. I don’t have to work - I would pay to come here.”

She set up the pre-school in an old school building across the road in January 1969, paying six shillings a week in rent. It moved to its present site in 1990.

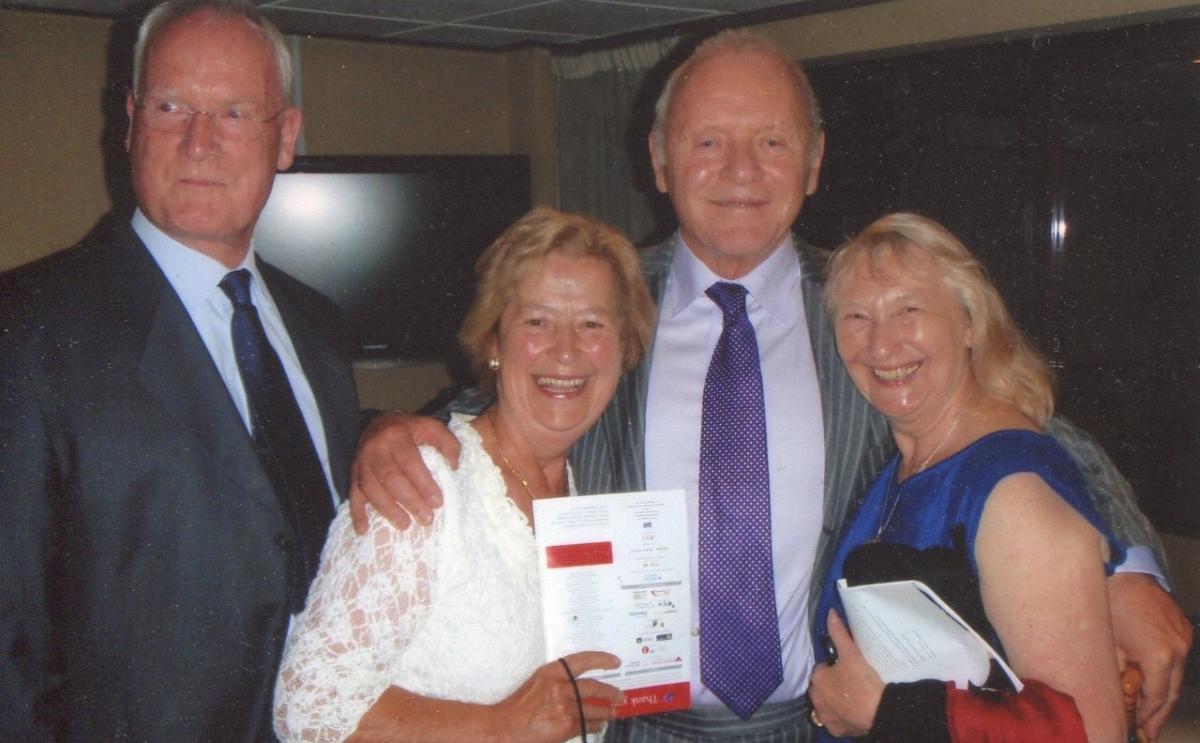

In a former life, Margaret was an actress. She studied at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art with Sir Anthony Hopkins. They starred together in Cat On A Hot Tin Roof in London’s West End in 1955.

“I could have stayed in theatre,” she says. “It’s similar to this - you’ve got an audience all the time. But I don’t think of it like that.

“I was Anthony Hopkins’ leading lady for two years. We still keep in touch. I was on the allotment with the children two years ago. I was told ‘Somebody called Tony’s on the phone.’ He said ‘It’s me, bach’ - that’s Welsh for little one, which is what he calls me - ‘how are you?’

“He’s had a difficult life. He can’t touch a drink. He becomes the person he plays. I said ‘What was it like when you were playing Hannibal Lecter?’ He said ‘I was only in it for eight minutes, if you look at the time I was talking.’”

Margaret’s conversation is beautifully varied, running headlong with a topic then dropping it and picking up another.

But when it comes to the children, she is utterly focused. If they are shouting over her or a staff member, she says “Zippy lips - quiet.” And they are.

A girl approaches and hands us each a small plastic cup with a straw stuck in something gooey. We thank her.

“What is it?” asks Margaret.

“A smoothie.”

“What’s in it?”

“Play dough.”

Very nice it is too.

In 1958, Margaret married the love of her life, Malcolm Bravo. They moved to Cumbria. Malcolm was head of languages at Carlisle County High School for Girls - later St Aidan’s School.

Margaret remembers vividly the night they met and how he asked her to dance. She beams when recalling the time he told her he had fallen in love with her.

“He was a lovely, lovely person,” she says.

When they arrived in Carlisle, Margaret volunteered at James Rennie School, for children with severe learning needs. She taught them speech and drama.

James Rennie pupils later attended her pre-school, twice a week for 27 years. “We’ve had a Down’s Syndrome child here,” she says. “The other children don’t see it. They just know that he’s fun.”

She points out a poster showing Elmer the elephant and his patchwork colours. The poster includes the words ‘But inside he’s just like us all.’

A boy comes over and says that he’s stood in a puddle. Margaret recites: “Dr Foster went to Gloucester in a shower of rain...”

She is then approached by a crying girl, and asks “Do you want a cuddle?”

The girl does. A cuddle is given and the tears quickly dry.

Margaret asks another girl about a recent journey. “How did you get from Carlisle to London?”

“We went on a big pirate ship.”

“On a big pirate ship? Are you sure?”

“Yes.”

She enjoys quietly keeping an eye on her children long after they have left here; long after they are children.

She produces a scrapbook of old photos, letters and cards. A faded letter begins ‘Dear Father Christmas.’

“He’s an online editor,” says Margaret.

She points to a boy in a black and white photo from 1969. “He has his own film company.”

Many pupils have been the children and grandchildren of those who came here decades earlier. Little girls and boys return as mums and dads.

“I recognise the boys more than the girls. The girls do all kinds of things with their hair. They all recognise me.”

Many are keen to keep in touch with the lady who filled their early years with kindness.

A wall is covered in paintings and pictures: gifts from children and parents. On Margaret’s birthday, cards pour in from around the country and beyond.

Some of the ways in which former pupils have repaid her are unexpected and priceless.

One morning in 2000, Malcolm died at home. He had been ill with cancer for five years. Just then, a former St Peter’s pupil called at the house to say hello.

“I said ‘Malcolm’s just died a few minutes ago.’ I knew he was dying. I said ‘What do I do?’ She said ‘Leave it to me.’”

Children in Cumbria are not the only ones to have been helped by Margaret. Horrified by the poverty she saw in a TV programme about India, she sponsored a doctor there.

After Malcolm died she visited the country twice to work with street children, blind people and lepers.

Since then she has also helped children affected by poverty and disease in Nepal and Brazil. A chance meeting with former Olympic athlete Steve Cram - now the chairman of children’s charity Coco - led to Margaret visiting Romania 11 times to care for children with HIV.

“I took musical instruments and make-up for face paint. I didn’t know how I would react to children with Aids. There was the fear of it then - people didn’t talk about it.”

To Margaret, they were always just children who needed love.

Back in the present, she asks a girl “Do you know the words to Frozen?” The girl begins to sing. Margaret calls two more girls over to form a choir.

St Peter’s is rated outstanding by education watchdog Ofsted. There is method here as well as spontaneous fun. Each child’s progress is meticulously noted in a book titled ‘Learning Journey’.

“This place is where they learn the basics,” says Margaret. “The focus is not on what they learn but how they learn.”

She watches captivated as two girls play with a toy egg and a toy pizza.

Does she have any plans to retire? “No - why would I want to retire? I’d be stuck in the house.”

Perhaps being immersed in youth keeps Margaret young and gives her the energy to keep shaping little hearts and minds.

Suddenly two boys are crying. Between sobs it becomes apparent that one wasn’t listening when the other was reading out a story, so the reader kicked the non-listener.

“You should have listened to his story,” says Margaret, who then turns to the other boy.

“And you shouldn’t have kicked him. We don’t kick people. Now, give each other a hug.”

They embrace and, for the second time in a few minutes, Margaret has stopped tears.

“Shouldn’t there be more love in the world?” she asks.

Yes, Margaret. There should.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel